The artist Corita Kent went by several names in the course of her lifetime. As a little girl growing up in Iowa in the 1920s, she was Frances Elizabeth Kent. On entering the order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (IHM) in Los Angeles, aged 18, she became Sister Mary Corita (the name likely a mistranslation of “little heart”). As she went from convent art teacher to unlikely pop-art star and vocal civil-rights activist, she was Corita Kent. Finally, on leaving the order at the age of 50, she became simply Corita. In her evolving identity is the story of a person committed to ceaseless creativity. In the vivid silkscreen prints and photographs she produced at the convent in the 1950s and 1960s, she was constantly cutting and resizing words, rejigging and reappraising them, inching closer to what she really wanted to say.

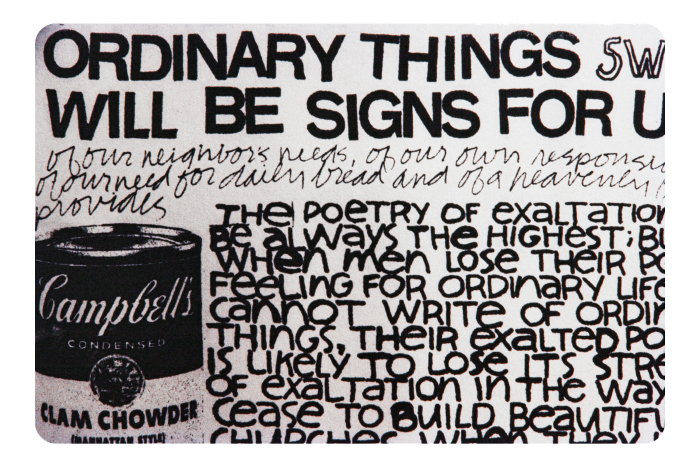

While Corita became widely known for her pop-art prints, this autumn a new book, Ordinary Things Will Be Signs for Us, explores a lesser-seen side of her work: her photography. Between 1955 and 1968, Corita took about 15,000 photographs, capturing the city, life at the convent and at the Immaculate Heart College, where she taught art between 1947 and 1968. Until now, the images have been stored at the arts centre set up in her name and available only on request. They reveal a world saturated with colour and joy. Whether taken on supermarket shopping trips, in the classroom or at the convent parade, they illustrate the keen pleasure Corita took in looking, one that she encouraged in her students. “There is whimsy and a lack of irony,” says Jason Fulford, who co-edited the book with Julie Ault. “It is clever and sophisticated, but not pretentious.” For Ault, this “fertile cache of images and ideas was a dynamic visual pool for Corita to draw from in her teaching, art and publications and also a vivid document of her life in the IHM order”.

In 1965, Corita wrote out 10 rules for her art students and pinned them to the classroom wall. “If You Work It Will Lead To Something”, they instructed. “Consider Everything An Experiment” and, in an extra-large typeface, “The Only Rule Is Work”. What do these newly uncovered photographs tell us about how she looked at the world? Here, 10 lessons for life from the pop-art nun.

1. Trust in the artist in everybody

Corita was born to a large, devout Catholic family in 1918, just a few days after the first world war ended. On entering the order of the IHM in LA in 1936, she studied for a teaching qualification, completed a masters in art history and started teaching in the college art department. It was then that she began taking photographs and making silkscreen prints. Many of the images in the book capture the banners and signs students made for the college’s annual Mary’s Day parade, a community celebration of the Virgin Mary.

2. Walk down the street with your eyes open

Corita looked at the world around her deeply and closely, always with a democratic eye. She would photograph mushrooms and pebbles, bright pink desserts, the splayed fronds of fern leaves and traffic cones cheerily touting flags, isolating their particular forms, textures and colours with her viewfinder. LA was a particular source of fascination: she once proclaimed that a single intersection of the city provided enough raw material for at least 16 hours of looking. “I think I am always collecting in a way,” she said, “walking down a street with my eyes open.”

3. Go home and come back tomorrow with 200 questions

Teaching in the Immaculate Heart College art department, Corita became known for her enthusiasm and rigour. Tasks might require pupils to make 200 line drawings of the same thing, or to come up with reams of questions in response to a film screening, while others recall “sitting around in a circle and each having a Coke bottle and looking at it for, say, an hour”. Corita would often take students on field trips to parking lots or the supermarket with empty photographic slide frames, encouraging them to home in on particular details, using her own photographs as examples. “Sometimes you can take the whole of the world in and sometimes you need a small piece to take in,” she told a group of students in 1967. “I think that is really what a work of art is: a small piece that you can digest, that gives you an idea of the richness of the whole.” Through her classes and lectures, she brought national acclaim to the small liberal arts college and was soon receiving visitors to her studio and lecture hall, including composer John Cage, architects Charles and Ray Eames and film director Alfred Hitchcock.

4. Be self-disciplined

Regular outings to see exhibitions in Los Angeles or New York by Mark Rothko (who crops up in Corita’s photographs), Jasper Johns and Robert Motherwell all fed into her practice. But it was seeing Andy Warhol’s first solo show of pop art in 1962, comprising 32 Campbell’s soup can paintings, that served as the major catalyst. Corita began to incorporate advertising signs and typefaces, which proliferated as American advertising spend boomed following the second world war, into her work. The religious impulse wasn’t gone — indeed, “I realised that anything that was any good had a religious quality, so that it didn’t matter whether it had that kind of subject,” she later said. So it was that the big, blobby dots on the packaging of the sliced white loaf Wonder Bread underwent a primary-coloured, Swinging Sixties revamp in Corita’s photographs and prints. By enlarging the word “wonder”, she hinted at the transformation that takes place during the Eucharist in the Catholic mass, perhaps suggesting how easily an earthly sustenance could be turned into something holy.

5. Look for a sign — then beyond it

She viewed advertising slogans with a playful eye: Instant Fels soap powder almost reads as “instant feels” in one photograph, while a glimpse into a bathroom shows a print by Corita under the toilet-roll holder which reads, in large letters, “extra soft”. Another shows a bright red car parked at a gas station on Sunset Boulevard; plastered on the wall beyond the vehicle, just visible through its side windows, is one word: “shock”. It’s a reminder that in her work, there is always a small jolt of surprise — the enjoiner, however kindly phrased, to look again.

6. Have faith in your faith

This approach could get her into trouble. One advert for Del Monte tomato sauce that read “Hang on, little tomato” inspired her to make her own silkscreen which described Mary as “the juiciest tomato of all”. She felt she was offering a fresh image of fecundity; critics thought she was being smutty. Chief among them was the ultra-conservative archbishop of LA Cardinal James Francis McIntyre, who resented the IHM sisters’ liberal approach. In 1959 he wrote requesting that Corita and her fellow nuns refrain from producing representations of the saints which were not “obviously reverential”. “Figures,” he went on, “that are burdened with a large element of uncertainty, as well as of the grotesque, are disturbing to pious souls.” But Corita was receiving validation from beyond the diocese. In 1966, the LA Times made her one of its Women of the Year, while in 1967 Newsweek featured her on its cover, along with the strapline “The nun: going modern”.

7. Come together when you can

Corita’s photographs are full of large groupings: children on merry-go-rounds, nuns parading or lunching. Nowhere is her celebration of community more obvious than in the pictures she took of Mary’s Day. This annual celebration was originally “a very dismal affair”, according to Corita, with students processioning around statues and saying the rosary. When she took it over in 1964, she changed the mood of the day, seeking to use it to “celebrate the real woman of Nazareth”. The result was a multicoloured, exuberant event, later dubbed by Newsweek a “religious happening”. (Cardinal McIntyre hated it, of course.)

8. Bid for joy

Corita was, by her own admission, “a demon for work”, but this didn’t prohibit joy — in fact, work was her best way into it. Another of her 10 rules is “Be Happy Whenever You Can Manage It. Enjoy Yourself. It’s Lighter Than You Think”, and in her photographs, the stark monochrome habits of the nuns stand in contrast with the vibrant balloons and confetti that filled her classroom. One picture shows her in 1967, laughing and exhilarated while carrying a tottering column of paper cups, her hair visible beneath a simpler, lighter version of the veil.

9. Why not give a damn about your fellow man?

As the 1960s went on, Corita’s work became more political, speaking out for civil rights struggles, against the Vietnam war or poverty in the US. One photograph shows a newspaper headline announcing “Mrs. King leads Memphis March, Pleads for poor”. Another shows an image of the word “stop” in a red typeface, foreshadowing her 1967 screen print “Stop the bombing”, made in response to the US involvement in Vietnam. “Living with people who were also socially conscious helped a lot,” Corita said of her political life. “I’m sure if I had been a nice, proper housewife, I would not have bumped into all of these ideas.”

10. Have a message

The images stop in 1968, the year Corita left her religious order after 32 years of service. The world around her had been changing, including the Catholic church: Vatican II, the great wave of reform announced in 1962, had led to deep ructions between conservatives and liberals. Corita was firmly in the latter camp, and eventually disillusionment with her superiors, as well as the sheer exhaustion of teaching and making work, led her to quit. She would pursue her own path, working on private commissions until she died of liver cancer in 1986. She never received the same acclaim as her pop-art contemporaries Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein or Richard Hamilton, but her mark can still be seen in the Boston skyline, on a vast gas tank she was commissioned to paint with a rainbow swatch of stripes. It attracted controversy after some onlookers protested that Corita, ever the anti-war activist, had snuck the profile of Ho Chi Minh into the edges of the blue stripe. Naturally, she denied the charges.

Louis Wise is assistant editor at HTSI

All images courtesy Corita Art Center

Ordinary Things Will Be Signs for Us by Corita is co-published by J&L Books and Magic Hour Press

Follow @FTMag to find out about our latest stories first