Elizabeth Nelson has a sensible attitude about painting outdoors in winter: She doesn’t. But you wouldn’t guess it to look at the body of work on her website. Among Nelson’s many landscape paintings are frigid-looking scenes in Iceland and Norway as well as Vermont. In a phone call from her home in West Glover, Nelson explained that she typically works from photos or memory.

“Some of the paintings are not literal,” she acknowledged.

Born in New York City, Nelson earned degrees at the Rhode Island School of Design and the University of North Carolina before migrating north more than 50 years ago. She lives on a farm now managed by her son and enjoys “a beautiful view of Mount Mansfield,” she said. Nelson is affiliated with a number of regional art venues, such as the Front in Montpelier, the Bryan Memorial Gallery in Jeffersonville, and AVA Gallery and Art Center in Lebanon, N.H. Her work is included in the Vermont State Art Collection.

Though she chose to live in a rural, isolated locale, Nelson has had her share of international adventures. During a visit to Reykjavik in 2012 as a tourist, she vowed to return as an artist. She was accepted for an artist residency with the Association of Icelandic Visual Artists in 2017, and a second one the following year.

“The landscape really spoke to my heart,” Nelson said. “My antecedents are Scandinavian, so that was familiar feeling.”

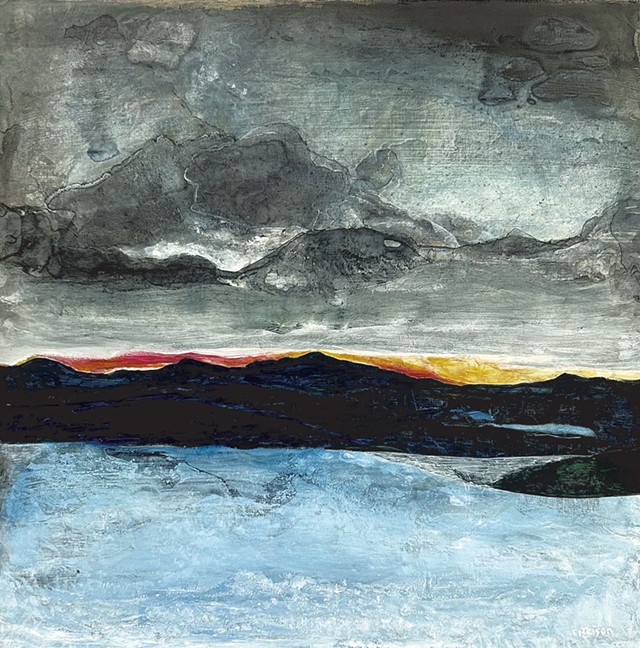

Her Icelandic paintings are, as she said, not literal; some are mere suggestions of blustery sky and frozen terrain. A 2019 voyage along the coast of Norway inspired Nelson’s evocative paintings of pointy mountains, fathomless fjords and remarkably animated clouds. In Vermont, her winter works tend to be more serene — or perhaps it’s just that the behavior of snow, bare trees and icy streams is more familiar.

Nelson doesn’t simply show us what winter looks like; she somehow conveys how it feels. It’s fitting that she’s the featured artist in an upcoming seasonal show at Furchgott Sourdiffe Gallery in Shelburne. For Seven Days‘ Winter Preview Issue this week, Nelson reflected on qualities of paint, light, color and snow.

Did painting in Iceland affect the way you paint in Vermont?

The thing about my time in Iceland was, it changed how I painted. I had brought acrylics and yupo paper rolled up in my suitcase. I’d been using acrylics — they’re fairly fluid. I would paint what I remembered from a scene, then go to bed. In the morning, I looked at it and … in a couple of places the paint did its own thing: Shapes and figures appeared mysteriously on their own. From then on, I let the paint do what it was going to do. It was a different attitude toward my work — much more exploring, taking advantage of what the paint and paper did together.

What are you looking for in a winter scene — what attracts you to paint it?

The light is very different. There are two kinds: a winter scene with snow, or a scene with no green — stick season. What appeals to me about winter, particularly with snow, is how it simplifies everything. The form of the land is more apparent. Snow reflects color in subtle ways. It seems more connected to the sky, so they are more of the same visual experience.

In a season where it’s not green but there’s no snow, I really find the subtle colors so fascinating. It’s like you can see the skeleton of the land. It evokes a response in me. I don’t want to make a copy of it; rather, it’s an emotional response.

You don’t actually paint en plein air in winter, but still the goal is to capture a sense of winter. What other factors are important to consider?

I like the drama of a storm, or what’s happening in the sky with snow clouds, the sun coming and going. Sometimes it’s the chiaroscuro, with strong sun on snow.

A nonartist might look at an expanse of snow and call it white. A trained artist looks at it and observes all the variations that light and shadow can create, no?

I don’t know whether I trained myself to see it; I’m aware of it and try to make it apparent to other people. I don’t know if it’s that conscious.

You paint what you see. In any event, those paintings of Iceland and Norway contain a lot of blue.

Iceland is particularly changeable — it’s always windy. That’s a factor just in living; it’s an awareness of the air around you. I’m aware of that out here in the country, too.

In some of your Vermont winter scenes, we see a field of snow interrupted by the dark silhouettes of bare trees. The drama is mostly in the sky.

I find that to paint the sky in relation to the earth is uplifting. It’s part of what I see. The earth doesn’t move around much. I like the motion in the sky. It is a mystery that you can convey motion, and emotion, with a little spot of color.

Your work has primarily focused on the northern landscape. Have you not ever wanted to just hightail it to a warmer locale and work with that different palette, light and subject matter?

Sure, I love traveling. I’ve been to Central and South America; the landscape is intriguing and fascinating, but it’s not my landscape. I’m happy to be in warmer places, but I’m happy to come home to the colder north. I’ve been here 54 years.

What appeals to you about it — visually or otherwise?

I like the changes of weather. And because of that, the landscape changes all the time. I like the agricultural landscape and forests.

You said your ancestry is Scandinavian; maybe it’s just baked in.

I went there with a friend with similar roots; we just wanted to see the landscape. It was bucolic, very Vermonty.

One of my primary reasons for painting this particular northern landscape is to try to communicate the beauty all around us and the need to value it. It is in increasing danger of being lost forever and is often overlooked in the rush and stress of life’s ever-increasing speed.