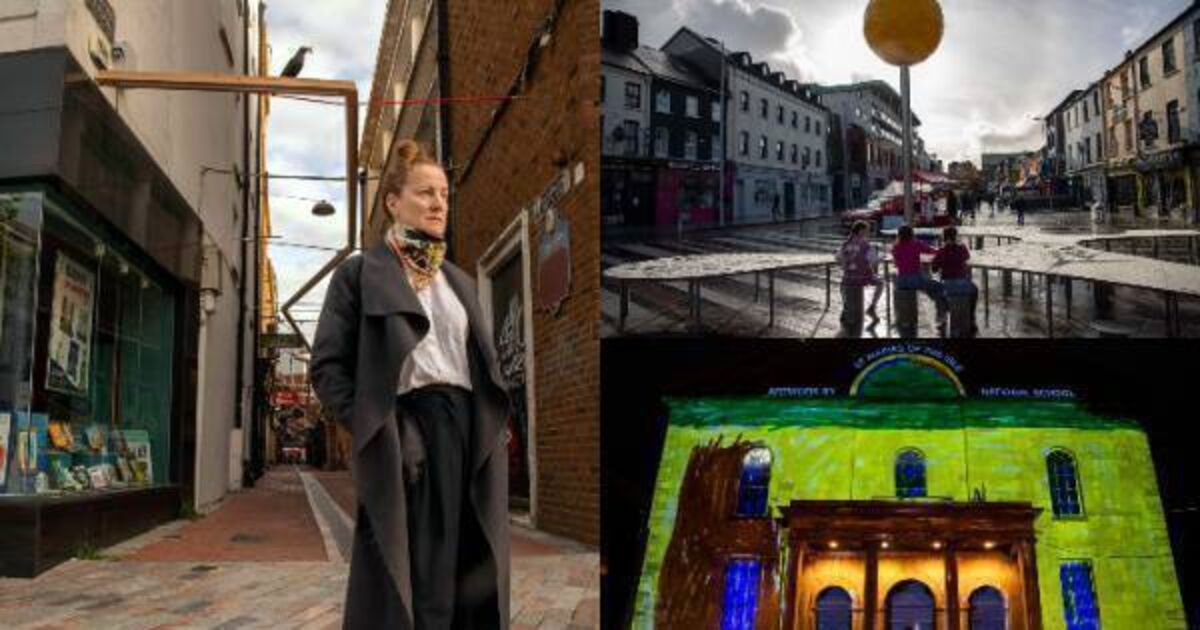

Island City is a trail of five artworks installed on the ‘island’ of Cork city centre between June and December 2023. The project was funded by Bord Fáilte under the Urban Animation Scheme, and commissioned by Cork City Council Arts Office, with support from the National Sculpture Factory.

With a budget of €670,000, it was the single biggest investment in public artwork in the history of Cork city. Four of the artworks were commissioned via a closed competition. This involved a number of artists being paid a fee for their proposal, one of which was then commissioned for each site. Their pieces will be in situ until at least 2028. The film projection at Triskel Christchurch was an open call, and will be replaced each year.

Reaction to the project has been mixed, ranging from appreciation and approval to indifference and disdain. Cork City Council arts officer Michelle Carew told us about the project.

The Island City project had a budget of €670,000. Has the city of Cork got good value for that investment?

Absolutely yes, I think. You’re looking at five artworks, or six actually, as we’ve already commissioned two for Triskel Christchurch. I think when you break that down, that actually does represent a very, very good investment.

But even to move away from monetary terms, I think the quality of the work that has been created, the artists that we’ve been able to engage, and the way in which we have been able to really forefront contemporary arts practice in Cork city centre, I think that’s all excellent value.

We’re really pleased to have been 100% funded by Fáilte Ireland. That’s a real mark of innovation on their part. I think they’re recognising the benefits of cultural tourism, that people want to visit cities that have something unique about them.

The nature of public art is that it’s in the public realm. People will have very strong opinions on it, and so they should. I suppose that’s always a consideration when it comes to commissioning, particularly as a public body, and being the local authority as well.

It’s very important that you have a very robust process in how you commission. You can go through the same process ten times over and come out with different results every time. You will never commission a work that everybody will agree on. But ultimately, I think that’s a positive thing. The worst outcome would be if nobody had an opinion at all, because then you haven’t made an impact.

For each brief we started with the site, and we provided some research on its cultural heritage. So, for example, with the site at Princes Street, on the Exchange Building, you had the culinary heritage of the street, but also the really interesting history of the Exchange Building itself, which was a theatre at one point. So all of that would have been in that brief.

Similarly, we looked at the heritage of the Coal Quay as a market and a meeting point. Each brief had very specific references to the heritage of that site. And then, of course, the submitting artists were also free to go off and do further research as well.

So, for example, with the Urban Mirror on the Coal Quay, it’s a meeting place. The work is designed to reflect that and be a place where people come together. The Face Cup on the Exchange Building; these were Bronze Age eating vessels along a street known for its dining, but also the resulting mask-like piece is a reference to the idea of drama and the masks of theatre and comedy as well.

So you can see in each artwork those hints of the reference. It was never intended to be a descriptive or educational interpretive piece about heritage. It was intended that they would be, first and foremost, original creative artworks, but that they would provide the public with a jumping-off point into the heritage of the area as well.

I would say that this was always intended as a trail, a project that would animate the city centre and serve as a visitor attraction.

The idea of dispersing the work, and bringing somebody on a journey, is really, really important. I’m not convinced that one single experience would have quite the same outcome, or whether that would even be the right thing for the city centre, in terms of a built-up area like that.

Also I think it was nice to be able to work with a wide range of artists, to support a number of different visions and help bring a range of ideas to fruition.

We subscribe to the Arts Council’s Paying the Artists policy. There are guidelines in terms of the percentage of the overall budget allocated to the artist’s fee. It’s very important that the artist is paying themselves, and they would all have ensured that there was an appropriate percentage kept for that.

The impression I have is that artists are very pleased to see that scale of commissioning happening in the city. The presence of contemporary art can only be a positive thing for the creative energy of the city. There’s a sense of Cork as a place to come to for contemporary art.

That wasn’t initially a curatorial decision. It was a condition of the funding that the works had to last for five years, so we then put that into the brief. But then, as we realised in the process, it actually ended up being a really interesting model for a public art commission, because by putting a time limit on it, it changes the context. The idea of permanency is a very overwhelming thing, both for audience and artist. You’re saying that whatever you make is going to be there forever, or, for the audience, that you’re going to live with it forever, regardless of how you feel about it.

By saying the works would be in place for a five year period, I think it encouraged the artists to be really ambitious and to take risks. It also allows for a changing landscape in the city, and it doesn’t commit anything to perpetuity. And who knows, maybe the plan is that the artworks will be decommissioned, or maybe it will make sense for some of them to stay, depending on how the city evolves with them and what the response is.

Valerie Byrne is Public Art Manager for Cork City Council. In her previous role as director of the National Sculpture Factory, she was deeply involved in the commissioning of the Island City artworks.

“It was always intended that the work in Carey’s Lane would be suspended overhead, and Niamh had this notion of taking a line for a walk, and drawing in the free air. She was looking at things like migration, the movement of people within cities, and the maritime history of Cork.

“The seagull featured in Sentinels is a recurring motif in Niamh’s work. She often plays with the notion that birds and animals are carriers of messages from other realms.

“Sentinels is monumental. If it were vertical rather than horizontal, it would be the same height as the Spire in Dublin. How often do we get to walk the full length of a street, under a sculpture of that scale?”

“Forerunner are a collective of three youngish artists (Andreas Kindler von Knobloch, Tom Watt and Tanad Aaron) based in Dublin. Their interest is in making art that has a function and encourages people to interact with it in some way, without being intimidated by the fact that it’s a piece of artwork.

“Boom Nouveau is a working light, and was always intended as such. But it’s a working light that’s been handmade by these three artists, utilising off-the-shelf materials, such as the girders and the cast bronze elements holding the glass. It’s showing us that objects we encounter every day on the streets can have a handmade quality and be beautiful.

“I love seeing that it’s already become a meeting point for people.”

“Fiona was working with the idea of a museum for everybody. An outdoor museum.

The Exchange Building is very old, and it’s a protected structure, so there were lots of concerns and considerations around not causing damage to it. Fiona’s piece is made of a resin fibreglass, and it’s hollow, so it’s very light. There’s a steel frame behind it holding it up.

“The work on based on the Bronze Age face cup and its attendant bowl and spoon that were found in an archaeological dig in Mitchelstown. The cup has a human face on it. The cup and the bowl have ears, but they’re facing in opposite directions. North, south, east, west. They were placed in a pit, so they may have had some ritualistic purpose. There’s nothing else like them in Ireland or Europe.”

“The brief for this site was for the artist to consider a pavilion, or a meeting space. Plattenbaustudio (Jennifer O’Donnell and Jonathan Janssens) are Irish, but their studio and practice is in Berlin. When they came to Cork, their overwhelming impression was that the Coal Quay itself, with its beautiful bowl shape, and the buildings all kind of circling the plaza, was the pavilion. All it was missing was the gathering space in the middle, a place to sit.

“Coming out of COVID, what we’d all noticed was that a lot of the street – and the pavement, with the outdoor cafes and so on – was very monetized. You had to be able to buy a cup of tea or a coffee to be able to sit at those spaces. So Urban Mirror was an offering to the city, a place where anybody and everybody can sit.

“The globe light is like one of those old-fashioned pins you’d stick in a map, as if to say, we are here. By night it illuminates, so you can see it from all around.“

Valerie Byrne: “We put out an open call for a projection onto Triskel Christchurch, and Brian Kenny was the first artist chosen. His work is really about climate change and climate action He invited the pupils at St Mary’s of the Isles to get involved, imagining a future for Cork and what that might look like.

“Brian also worked with the technology of the smart bikes close by. As people use them, that feeds into the work.

“Brian’s projection will end at the end of April, as the days get too bright for a projection over the summer. Elinor O’Donovan’s Winter Sun will then be installed in September or October, and that will run until April 2025.”

Valerie Byrne: “We want people to engage with this project over five years. We want it to continue to be something that might attract people to visit Cork, something to engage with while they’re here.

“We’re working on an app, and an engagement plan. A really important part of that is working with Arts and Disability Ireland; we’re looking at partnering with them to create an accessibility trail. So we’re working with specialists, developing QR codes for people who are visually impaired, with audio descriptions of each of the artworks. This is the first public art trail in Ireland that will be really considered through accessibility. It’s quite a complex plan, but we’ll have that by the summer.”