Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

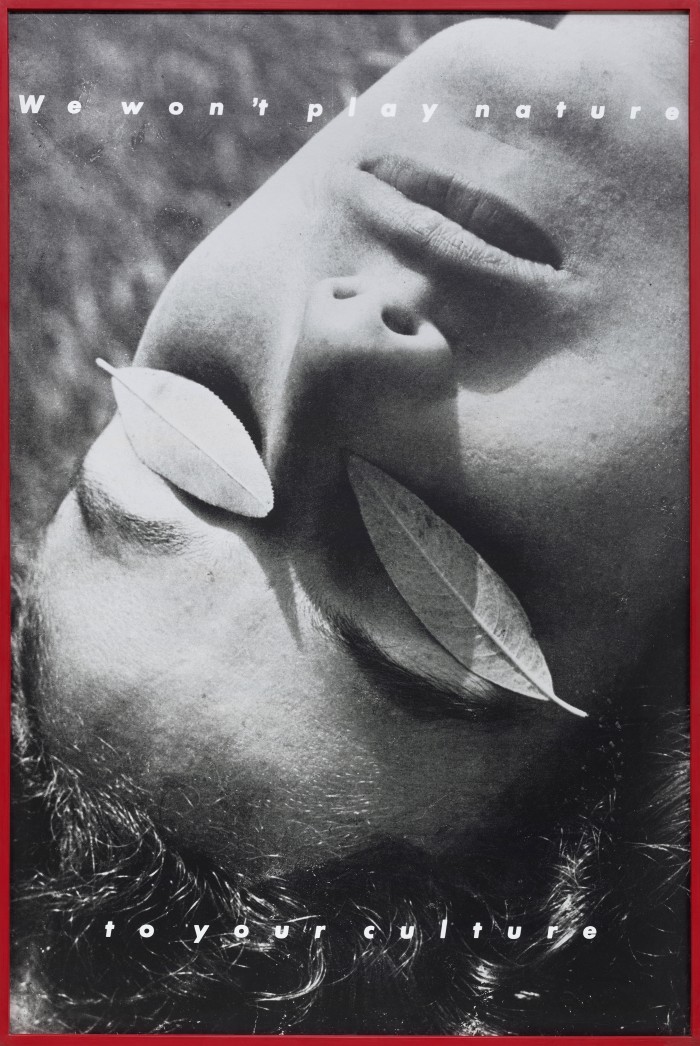

Barbara Kruger

‘Untitled (We won’t play nature to your culture)’, 1983

Barbara Kruger’s seminal work seems to me to embody the essence of this show. It contains this double rejection: of women being synonymous with (passive, silent, irrational) nature and of men as producers of culture. We see a closely cropped image, likely culled from a 1950s fashion magazine, of a glamorous woman lying against a grassy background with her eyes gently covered by leaves. The leaves make me think that she’s dreaming of another world: reimagining or willing into being a place that exists outside of the binary.

Minerva Cuevas

stills from ‘A Draught of the Blue’, 2013

These stills are taken from a beautiful, poetic film shot off the coast of Mexico in the resort town of Akumal. Cuevas invited two divers to descend into the Mesoamerican Reef to protest on behalf of the coral and marine life. They carry these banners with them, which read: “1%”, for the 1 per cent of the population that holds the majority of the world’s wealth; “Omnia sunt communia” (“all things are held in common”); and “25%”, the estimated percentage of marine life reliant on coral and “in trouble”. In the film, all you can hear is the “blub blub” sound of the divers’ oxygen.

The reefs are ecosystems that support innumerable forms of life and prevent flooding and coastal erosion. Cuevas is showing us the life in these reefs, which have their own architectural and sculptural beauty, but she’s also interested in the communities that live along the coasts and are absolutely dependent on their existence. So we’ve got this interlinked struggle for survival.

Simryn Gill

‘Eyes and Storms #1’, 2012

Singapore-born artist Simryn Gill’s Eyes and Storms series comprises 23 aerial photographs of open-pit mines, dams and lakes, most of which were taken from a light aircraft above the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Through her lens, the earth appears like a tortured landscape of scars, or “eyes” that have borne witness to ecological destruction. There are a lot of artists who take these drone-like, magisterial-gaze images from high up, looking down onto the world, and they can be incredibly seductive and sublime. But what Gill is trying to do is the exact opposite. She’s photographing fairly low to the ground and always at the time of day when the shadow is greatest, in order to give the earth a sense of corporality. You begin to see the hills and the mountains as the textures of a living organism.

Pamela Singh

left: ‘Pamela Singh, Chipko Tree Huggers of the Himalayas #74’, 1994 right: ‘Pamela Singh, Chipko Tree Huggers of the Himalayas #546’, 1994

Pamela Singh made these photographs of the Chipko movement (which means “hugging” in Hindi) in the villages of the Garhwal Hills in the Himalayas in Uttarakhand, northern India. She documented these women hugging the trees to protect them from felling by state and industry loggers who wanted to cut them down for timber. They were shielding the trees for nature’s sake but, more significantly, they recognised that their material survival rested on the trees because they used them for firewood, which heated their homes and allowed the women to cook. They also needed the trees to prevent soil erosion. The women saw that the violence that was potentially going to be enacted on the trees equated to violence that would be enacted upon their lives. It was a grassroots activist protest, which resulted in a 15-year ban on tree felling until green cover as restored.

JEB (Joan E Biren)

‘Planning session for 1 August action at the Seneca Army Depot, Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice’, 1983

Established in 1983, the Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice was a protest against nuclear weapons and military violence based at the Seneca Army Depot in upstate New York. Modelling their approach after the women’s camp at Greenham Common in the UK, the Seneca encampment drew participants from a large number of women’s peace groups.

Lesbian photographer and activist Joan E Biren (“JEB”) joined the movement to document the first summer of non-violent action at Seneca Falls, which was in protest against the deployment of first-strike cruise and Pershing II nuclear missiles to Europe. Through her lens, she gave visibility to the activists. In this photograph, we can see the women gazing directly at the camera; behind them is the barn, painted with figures dancing through a spider’s web. The web became a critically important motif of this feminist movement, because it denotes connectivity.

Susan Schuppli

‘stills from COLD RIGHTS’, 2022

In 2005, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights rejected a petition by Inuk activist Sheila Watt-Cloutier on behalf of herself and 62 Inuit people arguing for the right of ice to remain cold. They wanted to protect it for the sake of the ecosystem, but also as an essential element of the indigenous way of life.

Artist and researcher Susan Schuppli set out to make a film about the movement. She used footage taken in the Canadian Arctic, the Alps and Svalbard among other places, along with a spoken text to think through how legal systems could be used to advocate for the non-human. The resulting film asks what the disappearance of sea ice would mean for rising sea levels, but also easier oil extraction and the geopolitical implications for sovereign states as melting ice redraws borders.

Zina Saro-Wiwa

still from ‘Karikpo Pipeline’, 2015

British-Nigerian video artist and film-maker Zina Saro-Wiwa’s five-channel video installation “Karikpo Pipeline” depicts the Ogoni masquerade traditions in the Niger Delta in which young performers take on the bodies of antelope. She filmed them on the remnants of oil-extraction infrastructure and on the roads through Ogoniland, which locals refer to as “possessed” because they have been banned from using them by the oil companies. The video asks how spiritual presences might respond to a landscape shaped by oil extraction. “For me,” Saro-Wiwa says, “a Niger Delta environmentalism has to implicate invisible ecosystems, such as spiritual and religious beliefs.”

Laura Aguilar

‘Nature Self-Portrait #5’, 1996

For her black and white Nature Self-Portrait series, Chicana artist Laura Aguilar photographed her naked body in the landscape of the American west. By mimicking geological formations and natural elements in the land, imagining herself becoming a boulder or a tree, Aguilar becomes of nature, rather than in nature.

Ecofeminism was relegated to being a footnote in feminist theory because nature was seen as something to be dominated, and women were worried that if they aligned themselves with it, they were going to regress the movement. But now we have Laura Aguilar, recognising the radical political act of returning to nature. She’s able to see it as something that cannot be grasped or contained.

Ana Mendieta

‘Imágen de Yágul’, 1973

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the Cuban-born American artist Ana Mendieta used her own body together with elemental matter, such as blood, fire, earth and water, to create visceral performances and ephemeral “earth body” sculptures. In “Imágen de Yágul”, Mendieta places her naked body in an ancient Zapotec tomb at the pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican site of Yágul in southern Mexico. Delicate flowers appear to sprout out of her form. She’s asking us to reflect on the body’s inevitable demise while simultaneously underscoring the power of women’s bodies to create, sustain and nurture life. For me, it’s an attempt to resituate life on earth within an interconnected web of organisms.

“RE/SISTERS: A Lens on Gender and Ecology” is at the Barbican in London until January 14 2024

Follow @FTMag to find out about our latest stories first