They never met, and their lives followed very different trajectories. Yet a comparable inner energy seethes through the landscapes and cityscapes of two prominent artists who shared an uncanny artistic relationship. Londoner Leon Kossoff was a great admirer of Belarus-born Chaïm Soutine, who died aged 50 in 1943. Kossoff lived on until 2019, still working and exhibiting at 92.

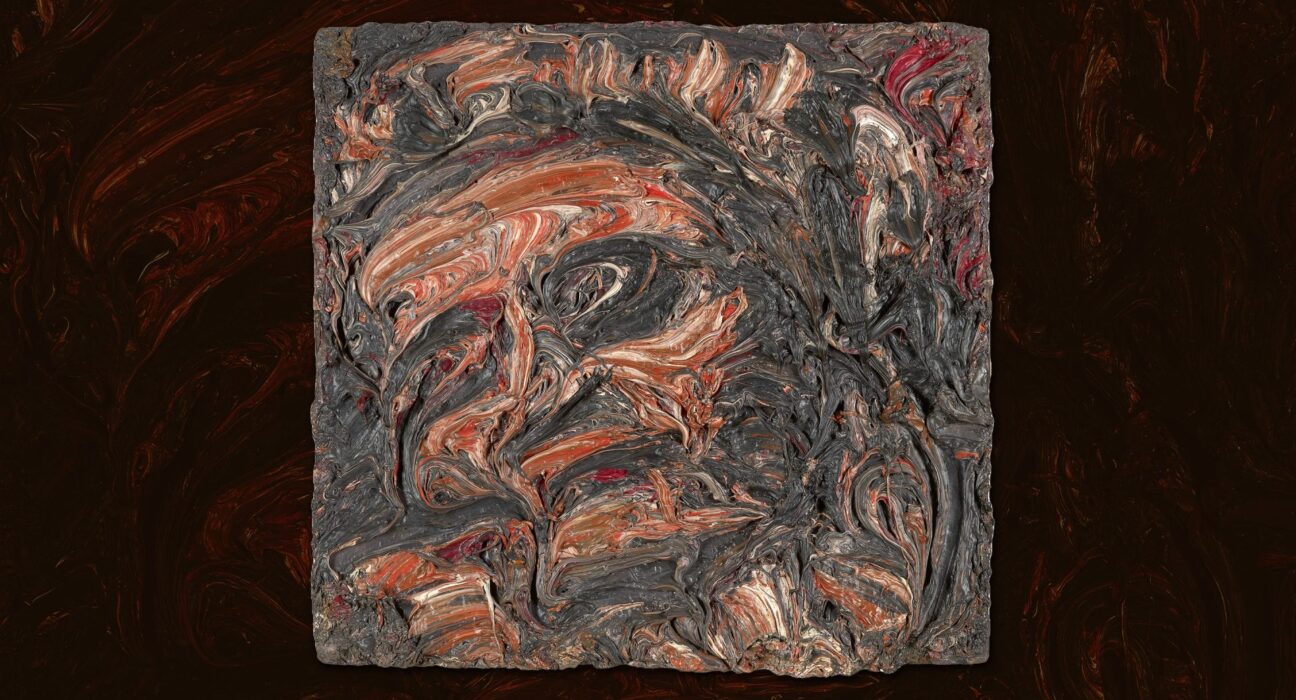

In paintings made during the first world war in Céret, in the eastern Pyrenees, Soutine invests turbulent plane trees with writhing power, dwarfing the lurching houses beyond. Half a century later, Kossoff wrenches new beauty out of the distorted detritus of wrecked buildings, heaving paint as gummy as mud and cement. He captures the ambiguous moment when it is hard to judge whether a building is coming down, going up, or complete and fulfilling its function. Demolition of YMCA Building, No 4, Spring, painted in 1971, City Building Site (1961) and York Way Railway Bridge from Caledonian Road, Stormy Day (1963) share the same thick accretions of paint. Only the demolition site lacks the purposeful lines that lead the way, its elements poised to tumble to flat ground.

These works are among several in an exhibition at Hastings Contemporary, celebrating the many parallels that existed between two complementary yet diverse careers – parallels that began in front of a single painting in the National Gallery in London. At the age of 10, Kossoff was captivated by the 1654 painting by Rembrandt in the permanent collection. A Woman Bathing in a Stream shows a model, probably Rembrandt’s common-law wife, Hendrickje Stoffels, standing carefully in water up to her calves, hoisting up her voluminous white chemise, other richly coloured garments crumpled in the background.

The model and the clothing are strongly reflected in water that may be clearer than it looks. Perhaps a pebbly riverbed cleans the flow, which would account for Hendrickje’s concentration, as she balances carefully and avoids sharp stones. Behind is an obscure glade fed by the brook, which in stronger light would appear more verdant. But a shaft of sunlight catches her contemplative expression. She may be pregnant: the couple had a daughter, Cornelia, in year the picture was painted.

The adult Kossoff’s own style connects strongly with the Rembrandt and its unexpected appeal to a small boy. The thick, sweeping brushstrokes that alchemise paint into linen, flesh, foliage and velvet must have seemed capable of magic. The viewer today zooming in on the image online can see the loose, fast brushwork that, magnified over and over again, atomises into complete abstraction.

Kossoff’s own handling of paint, 300 years after Rembrandt, practises alchemy of a different sort, with chocolatey swirls for limbs and muddy clumps for cityscapes. He copied the Rembrandt, but not, he maintained, for its painterliness but because, as he recorded at the age of 80: “Everything started from this picture… I remember thinking I could learn to draw from this painting.”

Soutine was so transfixed by A Woman Bathing in a Stream that he hired a model to re-enact the scene. In an episode reminiscent of John Everett Millais’ almost fatally jeopardising the health of Elizabeth Siddal in a cooling bath, for The Death of Ophelia, Soutine’s model was understandably grumpy about her equally chilly partial immersion for Woman Wading (1931). The work was painted five years before little Leon Kossoff stood in front of the original Rembrandt. Unlike Hendrickje, Soutine’s model has a distinctly grudging air in her downward gaze.

Chaïm Soutine was born to a clothes mender and his wife in Smilavičy, a predominantly Jewish town near Minsk in Belarus. Studying in Minsk and Vilnius, he was encouraged to move to Paris where he enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1913. Living cheaply among the other artists from many nations who were drawn to Paris at this vibrant time, he notably met the British artist David Bomberg, who was on the lookout for distinctive Jewish artists to feature back in London at a Whitechapel Gallery exhibition.

After the outbreak of the first world war, Soutine met the Italian painter and sculptor Amedeo Modigliani, who introduced his new friend to his dealer. The two artists escaped the bombardment of Paris by heading south to Cagnes-sur-Mer on the French Riviera, Soutine travelling on to Céret. In an extremely prolific period, he produced 200 works, but destroyed many of those paintings in the years to come. In 1920, his friend Modigliani died at the age of 35. But he lived on visibly in the portraiture of Soutine, whose subjects have the same singularity and soulful dignity as the friends, lovers and models who sat for Modigliani.

Filling the canvas, and with a frank gaze – even, in the case of Lady in Blue (1931), an exaggeratedly long neck, Soutine’s portraits speak to his dead friend. And it was through Modigliani’s dealer, Léopold Zborowski, that Soutine had the greatest of breaks: the American collector Albert C Barnes, founder of what would become Philadelphia’s world-renowned Barnes Collection, bought not one, nor a handful, but 52 of Soutine’s paintings. These he showed in his home town and in Paris. Soutine’s new, wider audience included the American Willem de Kooning, and in Britain, Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon – and Leon Kossoff.

Soutine was considered one of the School of Paris – an umbrella group of Jewish and other European artists drawn to the city. And in his turn, Kossoff was enrolled into the so-called School of London. It was a contemporary, the American-born RB Kitaj, who harnessed this term for an important exhibition curated by him at the Hayward Gallery in London in 1976 and dominated by figurative painters. For all their tidal waves of paint and energetic geometry, the paintings of Kossoff are, like Soutine’s, dominated by landscape – or, more precisely, cityscape – and portraiture.

Kossoff was born in Islington and raised in the East End of London, one of seven children of Wolf, a Ukrainian-born baker who settled in London at 15, and his wife, Rachel, also born in Ukraine. She was raised in London after crossing Europe with two siblings after her mother’s death. It is hard to believe that his family history did not have an effect on the determination and outlook of young Leon. Evacuated to King’s Lynn in the second world war, he was fortunate to be encouraged in his art endeavours by his host family, and he went on to study in London at St Martin’s and the Royal College of Art.

With marriage and the birth of a son, David, came the gift of seeing the world through the eyes of a child, while his early paintings of significance were inspired by the scars of postwar London. Views of shattered bomb sites, like carcasses with ribs and organs visible, prompted the thickly painted canvases with which he is most identified. Rarely speaking publicly about his art, he did vouchsafe, when asked why he painted so thickly, that it is “my natural way”. But it was the permanent way that formed a different thread in his work, especially when observing little David’s delight in the railway. Tracks career through the suburbs, swooping with giddying perspective past uneven dwellings that poke out like bad teeth.

The echo of Soutine in Kossoff’s life and career resounds again and again. In 1952, Soutine represented France in the 24th Venice Biennale; in 1995 Kossoff was featured in the British Pavilion of the 46th Venice Biennale. In 1963, an Arts Council exhibition featuring the young artist friends, Soutine and Modigliani, first staged at the Edinburgh Festival, was transferred to the Tate Gallery in London; in 1996 the Tate mounted a Kossoff retrospective.

Like Soutine, Kossoff encountered Bomberg, who taught him at the go-ahead Borough Polytechnic in south London. Years later Kossoff recalled that the older man told the aspiring painter that “the first 20 years are the worst”. Bomberg’s important painting The Mud Bath (1914), depicting bathers in Brick Lane, east London, must have been in his former student’s mind when he took little David for a swim. In Children’s Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon (1971) – owned, like The Mud Bath, by the Tate – Kossoff enjoys the mesh of limbs and bobbing torsos in the water, the dipping, diving, dancing figures lightly painted in and carefree.

Individual portraiture was a more tortuous undertaking for Kossoff. Models would recall that time after time he would scrape away the results of the previous sitting and start again. The writer NM Seedo was a distant relative, born Sonia Hussid in Romania. She sat for several paintings, including Seated Woman and the Head of Seedo. “The struggle that he was engaged in was nerve-racking,” she recalled. “He seemed to go through heaven and hell.”

The tussle with art never subsided, even though Kossoff knew great success in his lifetime, exhibiting at Tate Britain with Auerbach, Freud, Bacon and Paula Rego a year before his death in 2019. Recalling Bomberg’s warning that to become a painter took time, he retorted: “If he were here now, I would tell him that the first 50 years are the worst.” The entire lifespan, in short, of Chaïm Soutine, the artist whom he so admired.

Soutine/Kossoff is at Hastings Contemporary until September 24