T

he European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF) in Maastricht is the zenith of art fairs in quality, prestige, and cachet. Starting on March 7 and continuing this week, 270 high-end dealers gathered to offer their best to a crowd — TEFAF estimates that about 55,000 will attend — of serious, rich collectors, museum curators and directors, the art-curious, and at least one on-his-toes, eyes-peeled, beagle-nosed art critic. It’s a connoisseur’s fair but one where billions of dollars in art are ripe for the pickings.

I’ll write today about what I like the most about TEFAF’s art. The fair’s calling card is the fresh-to-the-market, leg-tingling, newly discovered, best-of-its-kind treasure. Often — but not always – these treasures are small enough to have been tucked away for centuries, though Titian’s Submersion of Pharaoh’s Army in the Red Sea, from 1514–16, is close to eight feet wide and four feet tall. Offered by David Tunick, this monumental woodcut of a cataclysmic scene does come in twelve sheets, so, while humongous, it’s actually compact if not assembled.

Titian (c. 1488–1576), who transcends time and words, isn’t known for prints. Submersion of the Pharaoh’s Army, done when he was in his mid 20s, might very well be a “quit while you’re ahead” moment. Topping it took 450 years, Cecil B. DeMille, Vista Vision, and splicing footage of the Red Sea with upside-down footage of water pouring from tanks. Titian did some splicing, too, since no wood block, sheet of paper, or printing press was that big. He had to conceive the totality on twelve blocks and, harder still, align paper, press, ink tone, and blocks. Eight of the twelve impressions are in museums.

Submersion of the Pharaoh’s Army resonated in Venice. Its swamps, estuaries, wicked tides, shoals, and hundreds of islands gobbled enemy after enemy. Today, Hamas and Hezbollah could use a good submersion, and I don’t mean on the big screen, and I don’t mean with upside-down tanks in a Paramount backlot.

William Ivins, the Met’s first curator of prints, once owned it. It stayed in his family until Tunick sold it in the 1980s. Now, it’s with Tunick again. In business since the late 1960s, Tunick himself has the master’s touch, with lots of repeat buyers and sellers. He’s probably wanting well over a million dollars.

There’s big, and then there’s tucked-under-the-pillow small. Galerie Chenel is offering a cameo, from the Julio-Claudian period (27 b.c. to a.d. 68), that depicts Agrippa Postumus. At 1.4 by 1.2 inches, it gives a dash of luxe, a sprinkle of yore, and a pinch of portent. Postumus was the son of Marcus Agrippa and Julia the Elder, the only child of the Emperor Augustus.

Some thought Postumus reckless, all thought him tough, and, though called depraved, he never had a specific scandal pinned on him. He might have been murdered on orders of the Empress Livia, who wanted her son, Tiberius, to succeed Augustus as emperor. Postumus died around the time Augustus did. Augustus, both calculating and squirrelly, might have planned to bounce Tiberius as his successor in favor of Postumus, by blood his nearest heir.

How do we know it’s Postumus? His cheekbones are high, and his chin is weak. He’s got a bruiser’s thick neck and big ears. His hair, each lock exactingly carved, is parted, pincer-like. The cameo dates to around a.d. 40, when the Augustan line faces were set to define specific personalities. Our cameo has the Postumus look. Sardonyx is a rare white-and-brown stone. Carvers meticulously manipulated its layers of color to create an image that’s iconic and lively. Here, the artist reserved the whitest parts of the stone for his complexion and his toga, with brown layers used for depth and volume.

The cameo first appears in records of the collection of the Earl of Bessborough in 1761 and, a few years later, among the ancient cameos belonging to the Duke of Marlborough. Sometime in the late 18th century, it was mounted in gold and semiprecious stones. The Seventh Duke of Marlborough, Winston Churchill’s grandfather, sold it along with most of his cameo collection in 1875 to pay the bills. The thing then bounced from collection to collection until the 1960s, when it landed in Switzerland, bought by an Italian named Sangiorgi.

This is what we want to see in Maastricht. The cameo hasn’t been on the market in 60 years. It’s exquisite, illustrious, and rare in subject, material, execution, and provenance. It tells of the perils of fame and fortune, nowadays one of my favorite topics. I’m told it’s “over a million dollars.” I saw lots of people at the fair with the means, style, and discernment to want to give Postumus the lovin’ he deserves.

When in art is a resemblance guaranteed? TEFAF offers lots of portraits, but I found two, both from the 19th century, one a sculpture, one a painting, both challenging photography’s claim that it is closest to truth. Photography was a new medium that, by the 1840s, both democratized portraiture and claimed the mantle of factual, unvarnished realism. At Dickinson’s booth, I saw Henri-Guillaume Schlesinger’s Ressemblance garantie, from 1853. The grinning, winning young man poking his head through the painted canvas wins over his day’s photography for warmth and charm.

Neither photography nor painting is reality. They’re representations by an artist with a quiverful of tricks depending on his take on his subject and, for portraiture, the connivance of his subject. Schlesinger was German, trained in Vienna, and worked in Paris. He sold Ressemblance garantie to the French dealer Goupil, who sent it to America. Dickinson is a London dealer. We don’t know where the portrait has been for the last 175 years. The sitter, who might have been an artist, looks like a Mark Twain character. He’s that fresh. It’s for sale for €120,000 ($131,000).

Prosper d’Épinay (1836–1914), who worked in London and Paris, specialized in polychrome sculpture. His painted terra-cotta sculpture of Françoise de la Rochefoucauld is an imaginary portrait of a French aristocrat from whom d’Épinay descended. She died in 1580. With pouty lips, eyes looking sideways, raised eyebrows, a lovely pink face, and a rich purple hat and turquoise coat, she looks eerily alive. Stuart Lochhead Sculpture, a London dealer, sold it to a Dutch collector for €120,000 ($131,000).

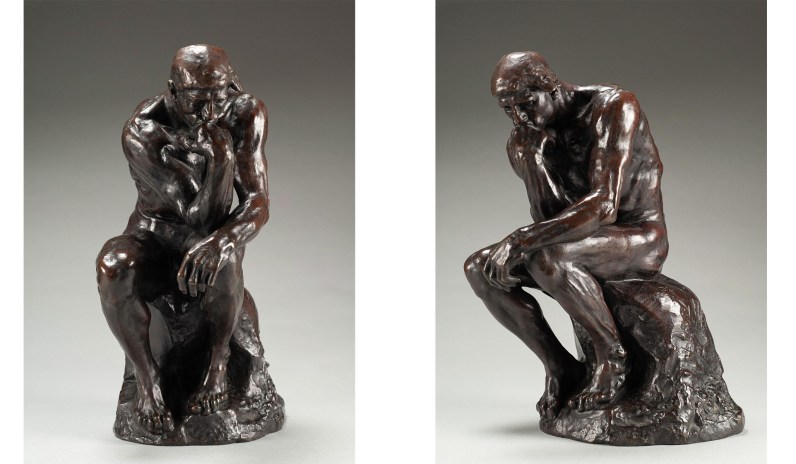

A bit bigger at 14.75 inches is Bowman Sculpture’s The Thinker, by Auguste Rodin (1840–1917). Yes, the image is universal, and so rampant, like Rodin’s The Kiss, that it’s high art, folk art, and kitsch all at once. Still, Rodin is the father of modern sculpture and our Michelangelo in depth and craftsmanship. Bowman’s Thinker is one of six known bronze casts made by Alexis Rudier’s foundry between 1903 and 1914 under Rodin’s supervision and specifically for the collector’s market.

The Thinker started as The Poet in The Gates of Hell, Rodin’s never-finished opus depicting aspects of Dante’s Inferno. Conceived in the early 1880s, The Poet has a place of pride among 180 figures and was meant by Rodin to evoke the unique power of the poet to conceive and to articulate the sins of humanity, among them the perils of love gone awry. The Kiss, referencing Paola’s and Francesca’s doomed fling, made its premiere in visual culture in The Gates of Hell.

Not long after he’d finished fiddling with The Gates of Hell, Rodin turned The Poet into a stand-alone figure, saying of him, “He is no longer dreamer, he is creator.” The sculpture was shown as The Thinker in 1889. Yes, it’s a tribute to Michelangelo and reimagines his religious fervor for a secular age. Intense cogitation is removed from divine inspiration. Adam, who lived naked in Eden, seems to be thinking outside the box.

The Thinker doesn’t deduce all day. He’s too ripped. I look at it as an icon of the individual’s power and authority, with the tension in how will becomes willfulness. I always think of Howard Roark from Ayn Rand’s Fountainhead when I see it. That’s a good thing. In high places are shouty nincompoops, men with overcooked linguine for spines, and animated meringues. We need more people who know how to think.

In any event, it’s gorgeous. Its provenance is fascinating. Howard Young (1878–1972) owned it. Young is the greatest art dealer no one knows. Out of his shop in the Pierre Hotel went El Greco’s Christ Healing the Blind, first to Charles and Jayne Wrightsman and then to the Met, and English aristocratic portraits to collections all over America. His nephew and business partner, Francis Taylor, was Elizabeth Taylor’s father. Young persuaded Dwight Eisenhower to run for president in 1952 and arranged his pivotal Scripps-media-empire endorsement. Young gave the Rodin to Ralph Harmon Booth, a Detroit grandee, and his fishing buddy, in 1926. Bowman got it from Booth’s descendants.

Bowman is asking €7.5 million ($8.2 million) for The Thinker. Forget about the Oscar, the Grammy, the Emmy, and the ugly thing called the Golden Globe. We need to make The Thinker the emblem for a new age.

I’d never heard of either Domenico Corvi (1721–1803) or Cesare Dandini (1597–1657), but there are a lot of Italians. I’m a scholar of American art and do indeed know that the New York dealer Nicholas Hall is famous for revelations. The Liberation of the Apostle Peter is a standard Old Master subject. An angel awakens the pope-to-be from a deep sleep to spirit him from prison. Goodness, we want good guys like Peter sprung. The bad guys need Soros-backed prosecutors for their get-out-of-jail-free cards.

Corvi’s picture from 1770 impresses for his pastel palette of lilac, lemon-yellow, and cotton-candy blue. It’s a nocturne with lighting from the angel’s halo. Even a gruesome Corvi, his Beheading of John the Baptist, also from 1770, shows the hateful Salome in a refreshing mint-green frock and a jaunty lilac cap with a teal bow. Both were Barberini-family commissions and have been in private collections since they were painted. They’re $120,000 each.

In Hall’s booth, the two Corvi paintings flank Dandini’s Still Life with Two Shelducks, from between 1637 and 1647. They’re dead ducks, to be sure, but in life must have relished their vivid, textured plumage, bright-red beaks, and handsome proportions, obviously toned even as they hang. Cardinal Gian Carlo di Medici commissioned the painting and liked it enough to move it wherever he went. The son of the grand duke of Tuscany, he enjoyed his military career before he was forced to occupy the Medicis’ traditional seat in the College of Cardinals. The American Charles Stuart Street bought it in Italy. From the early 1890s to the 1930s, Street was America’s eminent teacher and writer on the subject of bridge, knowing much about doubles. Hall wants $1,250,000 for it.

There’s size, and Dardini’s Shelduck painting is 32 by 17 inches, bigger than the two Corvis, but they have wall power, and then there’s weight, and there’s number. A. Aardewerk started more than a hundred years ago as a high-end antiques and jewelry shop in The Hague, but for the last 40 or so years has focused on antique Dutch silver as well as jewelry.

Whenever I can, I write about English, Irish, and French silver but rarely about Dutch silver, which has cleaner lines and, the Netherlands being a great naval power in its day, inspired by the shape of waves. No waves are involved, though, in Aardewerk’s extraordinary set of 16 candlesticks, with two sets of wings for two candelabras, from 1785 to 1787, all with an applied coat of arms. They’re elegant, with neoclassical decoration like beading, acanthus leaves, and garlands, and I’d describe them as Louis XVI style and similar to French and English candlesticks from the 1780s.

What’s amazing is that the set has stayed intact for nearly 240 years. Death and inheritances divide sets. In flat, little, prosperous Holland, invasion, conquest, pillage, and privation are not unknown. This family of 16, together weighing 13,836 grams, or 488 ounces, or more than 30 pounds, has stayed together. The set stays together for a mid hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Less is more, and good things come in small packages, but sometimes size matters, and the bigger the more astounding.

TEFAF in Maastricht is changing, alas, though I saw lots more art that, like these examples, make it unique. Another day, I’ll write about some of the new directions I saw. I’ll be ranty.