In 1890, the Lumière brothers were in the process of inventing the cinematograph which would turn into cinema as we now know it. During this time, Claude Monet started devoting himself to the execution of several painting series. These series featured work that showed the same subject, often from the same angle, during different times of day and different seasons. Monet began with the Haystacks series, then moved on to Poplars, the Rouen Cathedrals, and finally his famous Water Lilies. These series are unique, and predate time lapses. Read on to learn more about why Monet choose to paint the same subjects over and over again.

1. Claude Monet’s Haystacks

In 1883, 40-year-old Claude Monet was the leader of French Impressionism who retired to Giverny, Normandy. Isolated from the public and other artists, his art took a unique turn in 1890 when he devoted himself to painting what would become several famous series. It was perhaps while painting several versions of The Gare Saint-Lazare in 1877 or The Petite Creuse in 1889 that Monet came up with the idea for these artistic experiments.

This artistic period began with Haystacks, a series consisting of more than twenty paintings. As early as 1888, Monet began to paint the haystacks near his Giverny home. The goal of this repetitive series was to show the different effects of light and atmosphere during various days, seasons, and weather conditions. Sometimes the framing and point of view would vary. With this new goal, Monet abandoned landscapes. He started focusing on fragments of the landscapes instead.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription

Thank you!

In May of 1891, Monet presented fifteen of the twenty-five paintings of this series to the public for the first time. This was done during an exhibition organized by the Paul Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris. In Daniel Wildenstein’s Catalogue Raisonné of Monet’s works, the numbering on each painting is generally the one used to refer to each of the artist’s paintings. This numbering makes it possible to differentiate between the numerous paintings in each series that have the same title. For the Haystacks series, the paintings are numbered W1266 to W1290.

These paintings perfectly illustrate the way the Impressionists perceived color. Knowing that every color has its opposite, Impressionist painters associated each tone with its complementary color in order to highlight it. The eye then on its own reduces the disturbance of contrasts and operates an optical mixture based on the complementary tones. This allows for the disappearance of the painter’s palette, with the eye performing the mixing of colors itself. This idea was theorized by French scientist Michel-Eugène Chevreul in his law of simultaneous color contrast, which inspired both Impressionists and Pointillists.

The haystacks were painted at various times of day which allowed Monet to experiment with this color theory. He studied the variations of light during the day: morning glow, afternoon sunbeams, and the evening sky. In some paintings, Monet also painted the effects of light and colors specific to each season and weather condition. In Grainstacks (W1273), the application of Chevreul’s color theory is undeniable. The blue used for the tip of the haystack in the shadows complements the various orange tones used to represent the sun’s rays and their reflections.

Monet and the Impressionists did not want to faithfully depict the conventional appearance of objects. Instead, they tried to interpret them in their own way. By doing so, they suggested a new definition of painting as a field of expression where vibrant colored sensations could be achieved. Monet advised inspiring artists not to look at the objects in front of them as references for painting, but to instead look at them as spots of color. This advice makes sense when looking at paintings from the Haystacks series, in which even the shadows are treated with bright, pure, and unmixed colors.

The Haystacks series perfectly illustrates the progressive evolution of Impressionist painting. Some canvases still retain a certain degree of naturalism, a fidelity to painted reality, like the first painting in the series called Haystacks, End of Summer (W1266). But in other works, Monet’s technique starts rejecting volumes and details and becomes solely interested in tactile and luminous effects. The brush strokes thicken and the forms dissolve. Spectators are faced with paintings that express the painter’s emotions much more than the original subject. One of the last paintings of this series, Grainstack in Sunshine (W1288) allegedly dazzled the young Wassily Kandinsky during an exhibition in Moscow in 1896.

In 1969, the famous pop artist Roy Lichtenstein paid homage to Monet’s Haystacks with his own series of 7 lithographs sharing the same title. His own Haystacks depict, like those of the Impressionist artist, the variations of light at different times of the day, thanks to a scale of colors ranging from yellow in the morning to black in the night. Monet’s experiments with colors and his avant-garde version of screen printing had a tremendous impact on the development of Modern Art. Lichtenstein would further explore this extraordinary artistic dialogue with the Impressionist master. Indeed, over the course of his career, the pop art icon produced two other series of lithographs inspired by some of Monet’s paintings from two series: Rouen Cathedral (1969) and Water Lilies (1992).

2. Poplars

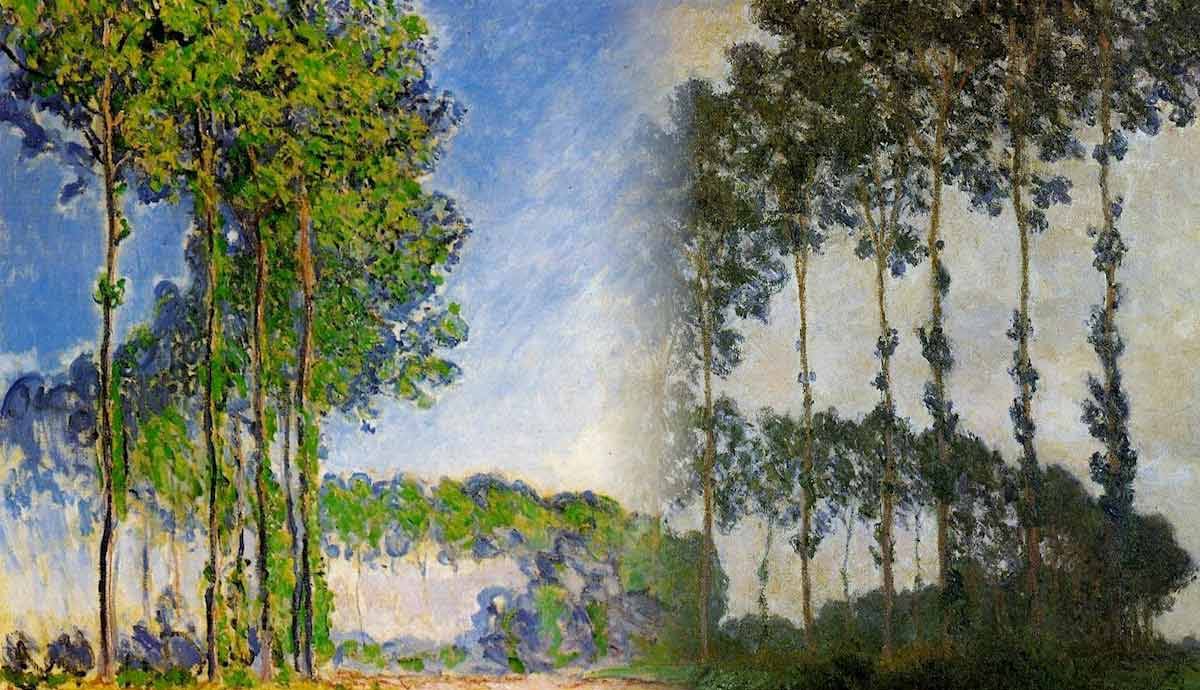

Between the summer and autumn of 1891, one year after Haystacks, Monet produced a new series of twenty-three paintings called Poplars. While the Haystacks series varied considerably in terms of angles, framing, and canvas formats, this series is much more consistent. The canvases emphasized the trees that stood up to the sky.

Like Haystacks, this new series picks up the Impressionist principles that Monet never ceased to defend and illustrate: open-air painting where one could draw directly from the subject during a particular moment in time. Monet tried to capture the moment in this series by painting shadows, marking the movement of the sun and the cycle of days and seasons expressed by the variations of colors. However, his depiction was not scientific or realistic, but rather created in order to translate a personal impression. Thus, the naturalistic accuracy of these shadows or colors is sometimes questionable.

By observing the changing hours, days, and seasons in his series, Monet focused on what captivated him the most: the effects of light. By trying to paint these effects, he sought to capture the ephemeral. This is why the subjects he chose were always simple and why details were absent from his paintings. Only light and colors were what mattered. The subjects can even appear blurred, and a few brush strokes were sometimes enough to sketch a shape.

For Monet, a landscape is not immutable but subject to infinite atmospheric variations and versions. He explained this to Dutch librarian Willem Byvanck in 1891: Here is what I proposed to myself: above all, I wanted to be true and exact. A landscape, for me, does not exist as a landscape, since its aspect changes at every moment; but it lives by its surroundings, by the air and the light, which vary continuously […]. You have to know how to seize the moment of the landscape at the right time, because that time will never come back and you will always wonder if the impression you captured was the real one.

3. Rouen Cathedrals

The Rouen Cathedral series consists of 30 paintings that Claude Monet made between 1892 and 1894. He mainly painted the western portal of the Notre-Dame de Rouen Cathedral, from different angles and at different times of the day. Monet wanted the paintings of the cathedral to be seen together, as an ensemble.

In 1895, Monet selected 20 of these works to be exhibited in his art dealer’s gallery in Paris, as he did with Haystacks several years before. The exhibition received a mixed reception from critics because of the religious character of the building being represented. Some, however, saw a dreamlike quality in the way the light played with the facade of the cathedral. Monet’s choice to study and paint the facade of the Rouen Cathedral, which is a very elaborate and complex piece of architecture, seems unusual. He generally preferred sticking to simple subjects devoid of details to be able to devote himself to the study of light and colors.

These paintings are, however, reminiscent of the way Monet treated the chalk surface of the cliffs of Étretat a few years earlier. In order to capture the atmosphere and light hitting the stone surface, Monet experimented with pigments to try to achieve the desired colors. The facade of the Cathedral was carved out of monochromatic stone, but Monet’s paintings display many colors, ranging from shades of mauve and green to pink and orange hues.

Rouen Cathedrals features a rare urban subject among his series strongly anchored in nature. Its architecture, the shadows cast on its facade, and the variations of colors and textures on the stone are elements that allow Monet to apply his Impressionist principles to this urban subject. A few years after the Rouen Cathedrals, he once again put aside rural subjects and chose the Parliament of London as the motif for a new series of 19 paintings. These two series are his most in-depth studies of light and color in architecture.

4. Water Lilies: Claude Monet’s Final Masterpiece

Following the opening of Japan to Westerners in 1853, the wave of Japonism took over Europe. European travelers started exploring the country and bringing back objects such as tea, engravings, and clothes. Monet himself was fascinated by Japanese culture. The artistic period he dedicated to his painting series seems to be indebted to his keen interest in the Japanese art of ukiyo-e (Japanese woodblock prints and paintings).

Monet even owned a large collection of Japanese art, which he used to decorate his home in Giverny. The very principle of making a series of works is common to famous Japanese artist Hokusai who notably produced the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji between 1831 and 1833. It is widely believed that Monet was heavily influenced by Hokusai, along with other Japanese artists such as Hiroshige.

Water Lilies is a series consisting of approximately 250 oil paintings produced by Monet during the last 31 years of his life. Water Lilies is also the final and largest project of his life. These paintings show the pond of water lilies from the flower garden of Monet’s house in Giverny, which now houses the Claude Monet Foundation. Designed by the painter himself, this garden serves as proof of his love for Japanese culture. It has a Japanese footbridge covered in wisteria, water lily ponds, weeping willows, and bamboo forests. Monet drew his inspiration from this garden for more than twenty years. The paintings of the Water Lilies series vary in shape and size.

Monet explored all the potential of the aquatic reflections. But the real subject of these paintings is, again, light. Monet painted it with a rich palette of colors that brought its reflections in the water to life. He juxtaposed complementary colors like yellow and purple, which accentuated the sensation of a luminous radiance and expansion of space in the spectator’s eye.

Like in the Haystacks series, the initially figurative Water Lilies paintings became more and more abstract over the years. Not unlike the irony of Beethoven going deaf, many of these canvases were painted while Monet was suffering from cataracts and when he slowly started losing his eyesight. His increasingly cloudy vision produced unreal and dreamlike paintings. His garden’s Japanese footbridge was the subject of many of his paintings, but the way he depicted it changed considerably over time. In 1899, Monet painted a very realistic version of the bridge in The Water Lily Pond (W1516) with serene shades of green. The Japanese Footbridge, Giverny (W1932), painted about twenty years later, on the other hand, shows an amalgam of bright red, orange, and yellow shapeless colors in which the spectator can hardly make out the shape of a bridge.

Echoing his Impressionist theory that landscape painting should focus on the correlation between light and color, Monet could no longer see the details of the subjects he was painting. He truly reached the vision of landscape he advocated: to be able to observe his environment as patches of color, without shapes or details. In his Water Lilies, the strength of his creative gesture and the broad treatment of the entire surface of the canvas without distinguishing different planes are all elements that would later seduce the young American artists of Abstract Expressionism.

From 1914 to 1926, Monet worked on a large set of eight panoramic paintings intended to be a gift to the French government as a symbol of peace at the end of World War I. This work represented the culmination of his Water Lilies series. Conceived as a cycle of paintings and created for a specific place, the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, this series of Water Lilies is now permanently hung in the museum according to Monet’s instructions. The canvases are placed on the walls of two oval rooms, lit by natural light.

This project isn’t a classical representation of a landscape. The artist fully explored the possibilities of color and touch. From a distance, the touches of color recompose the image of a body of water without a shore or a horizon. Up close, the spectator can see the pictorial matter above all. This unique ensemble is a true Sistine Chapel of Impressionism, which the painter André Masson said in 1952. It testifies to Claude Monet’s last artistic project, designed as a real environment and the end of the Water Lilies series. The Musée de l’Orangerie’s Water Lilies is one of the largest monumental painting projects of the first half of the 20th century.